"CRUX OF THE MATTER"

Non-Sectarian

Crucifixion Archetypes

Interview with Antero Alli

by Jonnie Gilman; November 1999

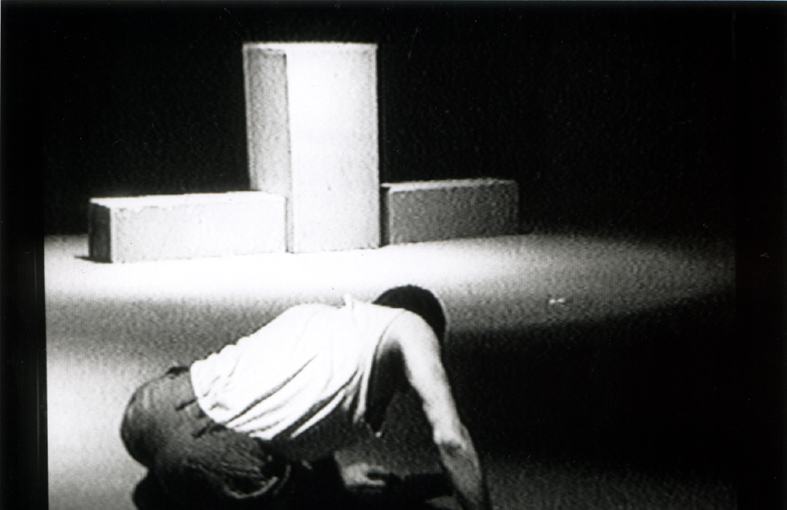

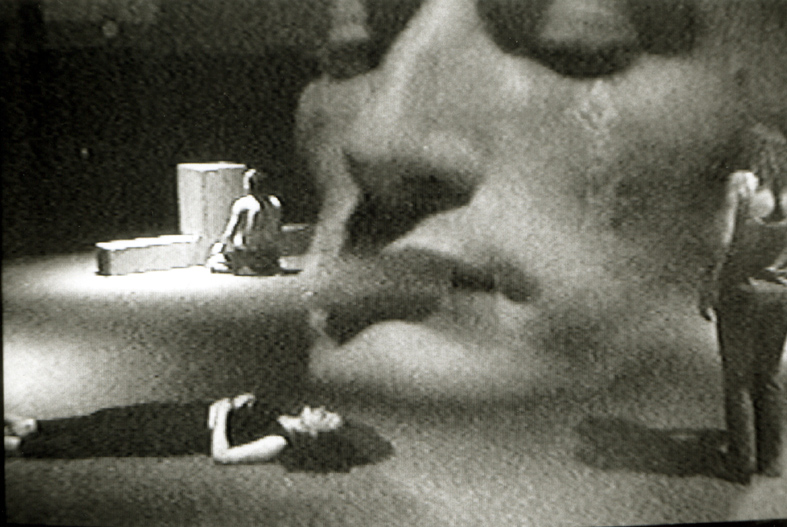

This interview followed the

paratheatrical CRUX lab that met three times

a week for five weeks

in Berkeley during the summer

of 1999. I made an

82-minute video document, CRUX,

of some of the

rituals and participant

reactions

to their experiences.

This interview was first published in the

(now defunct)

Seattle tabloid,

INSTANT PLANET. -- Antero

Alli

JONNIE

GILMAN: Did you find with the people

participating with the ritual that they had a strong

charge to the symbol of the cross in and of itself

and did that get in the way?

ANTERO

ALLI: Yes and no. The charge was was much stronger for some than others yet no one escaped its mysterious magnetism. My assumption around the symbol of the

cross is that it has deep historical relevance,

as well as, profound psychological, spiritual and

religious charge. Oftentimes much deeper than what

we're aware of. As a species we've spent the last

couple of thousand years in various forms of religious

warfare, acting out various opposing and conflicting

vantages of what the cross means. The crux of one

culture differs from the crux of another culture,

and if you have conflicting cruxes that face off

with each other, the horror of war can be ignited.

I'm using the word crux here to symbolize a point of worship, meaning what an individual life or a culture revolves around; what it lives for. Sometimes it can be broken down to: "what am I living for?" What is a particular culture living for? If you honestly ask that question of yourself, you can begin tracing your responses back to a crux -- a point of worship -- of what your life actually revolves around - not what you hoped it might revolve around but what you actually live for.

In this CRUX project, I avoided intellectual

or philosophical discourse on the religious symbolism

of the cross. Instead, I presented the cross as a symbol

for what the crux might represent to each individual

without binding it to any historical, religious

or metaphysical context. If these levels came up

on their own, then fine. But to fill our minds with

past crux references would only impede a more authentic

response. I was afraid these past references might

overwhelm and interfere with the exposure and expression of something more personal. So, I introduced

ritual triggers to this group that provoked, in

bits and pieces along the way, elements of what

might lead to their personal crux.

The reason for presenting it in bits and pieces

was that oftentimes people have a concept of what

they're living for, or an idea, or even a belief

but when actually confronted with the psychological

pressures innate to the reality of what they are

living for, those previous concepts often break down.

At that point, you either let go of those images

or suffer a kind of psychic immobilization and crucify yourself

on a dying concept. And this happened, to some extent,

with everybody. Fortunately, everybody also had

many opportunities to outgrow their obsolete ideas

of the crux and restore their psychological freedom.

Once you confront the crux as direct knowledge

or an impression of a living energy and force within

you, it's difficult to deny its existence. Consequently,

there is often a kind of ego death in that confrontation

and a need to redefine

and rethink what you are living for. This crux process

is an ongoing one, a kind of life work. It's not

like, all of a sudden everybody gets their crux

and that’s it. (laughs) Far more often than

not, it involves going through many layers of the

crux until you get to something that makes itself

evident by the force and the energy it imparts to

the life you are actually living. You see, the crux

energizes you.

JG:

The crux seems to be a symbol of the individual

in and of themselves, embodying the horizontal and

the vertical, that forms the crux. The individual

living entity finds himself in the center of these

pulling, pushing equalized forces. They are right

there, stuck. Even though you are getting away from

the crucifixion, its like you are pinned to your

cross in that way.

AA: In this group experiment we discovered a certain irony to that solitude. By confronting our own individual crux, we saw how we were also connected as a group. We looked around and saw how we were all nailed to the cross of our own existence; we’re all crucified somewhere. Everybody’s stuck somewhere. That sense of unity, I think, bonded the group. So, this wasn't a self-isolating ritual. It actually promoted a deeper group unity but to get to that unity we had to penetrate our own individual crux first and that meant arriving at some pretty intense and painfully lonely places where we were righteously stuck. You know, there's a fine line between a rut and a groove and the deeper the rut, the closer the crux. By the way, this whole notion of being deeply stuck or nailed, was never presented with any incentive for "self improvement," or getting “unstuck” but as a symptom of getting closer to center. The oervall incentive was self-knowledge and maybe, self-transcendence but not without serious self-confrontation.

The word "crux", is

a mountaineering term for the most difficult passage

on the way to the top of any mountain. This tough

passage is called the crux because if you get through

it, you can reach the top of the mountain. If you

can't get through the crux, you have to return to

base camp or, get stuck in the crux.

JG:

Its a kind of birth canal.

AA:

I relate more to the mountain metaphor. I mean,

here was this group on the way up to their own existential

peak, to discover the edge of whatever they are

living for and each climber had to confront their

most difficult passage to get there or, climb back

down to base camp.

JG:

There is no way to go back to sleep once you have

that knowledge.

You can't not know that.

AA:

That depends on the degree you wake up. It’s

easy to slip back into sleep, so to speak. I think

that without some kind of ritual device or catalyst

or drug or accident to force or shock us back into

the heat of our crux, it is easy to fall asleep,

again. We learned to create our own pressures and

ways to keep the heat up to stay awake enough to

keep one eye on the peak. Maybe it’s an acquired

taste for difficulty, a certain excitement for meaningful

struggle. Not all struggle or difficulty proves meaningful.

JG:

Watching the video, I was struck by the intense analysis

that people would go into to try to understand what

their motivations were, or what was the heat for

them, why they were here, and, in some cases it

seemed immobilizing. There's a certain fixed quality

to that because in the midst of all these opposing

energies, self conflict, getting kind of lost in

a mental realm of analysis.

AA:

Direct exposure to the crux point can shock the ego. And one common reaction to that

shock you can see in this flailing about for answers

and grappling for some kind of conceptual understanding.

I think this is a natural way ego attempts to restabilize

itself after the shock, to get back in control and

make sense of something larger than our mental

categories. Sometimes ego can tear this experience to tatters. Lke a hungry dog attacking a steak, it can become

morbidly obsessive with creating certitude or control where there may be none. This shock to ego is really

an exposure to the possibility that some part of

you lives for something other than ego. Ego doesn't want to hear that. What a blow to vanity! Ego wants

to believe that IT's what you are living for. Ego

wants to believe that IT's the most important thing.

And so ego

will try to come back and impose some understanding

of what's happening in an attempt to regain false

control.

Everybody went through some degree of this ego drama. These

fixations on explanations came out more in the beginning.

The more you go back to the direct experience of

the crux, however, the more that experience softens

those fixations to try and explain everything. As people

were subjecting themselves more and more to the

exposure of their crux, they tended to grow a little

easier around that compulsion to understand everything. There is real mystery in the

crucifixion archetype. Over time, I saw more acceptance

of that mystery and more ease with simply being in it,

rather than needing to understand it. Some people

showed more die-hard ego struggles than others by clinging

tightly to their dogmas, trying to conform their

experience to previous beliefs which only added

to their suffering. Sometimes, the crux hurts.

JG: The need for

answers is perhaps a form of resistance.

AA:

For some, it can be a brutal revelation to be exposed to what you are actually living for, as opposed to what you think or hope you're living for. If you have a negative reaction to what you're living for it can be like waking up to a nightmare. To live with that knowledge is obviously very challenging. The only creative thing you can do at that point is muster up the courage to show yourself some compassion to live with more truth about yourself. Sometimes you find out what you are actually living for and are genuinely excited by that. That's not hell; that’s heaven. But if you are waking up to anything you are not ready to live with yet, that may as well be hell.

JG: Once people grew conscious of what they’re

living for and it was distasteful to them,

did it

compel them to shift that core of what they are

living for?

AA:

Each person reacted differently to that incident.

Some people would just bury their head in the ground

ostrich-style and try to escape or deny and pretend they didn't

see it. Others would surrender to the fact and agree

to suffer and experience remorse or shame or whatever honest emotional reaction they needed to experience

to what they were living for. And I respect that.

Maybe they discovered how they had settled for less

and felt bad about that. One person

discovered that all she was living for was sensation.

Her whole life amounted to producing more and more

sensation. Pleasure or pain, it didn't matter. Just

as long as more sensation was produced. When she

first discovered that, she became depressed. She

very much wanted to believe that somewhere deep

inside there must be something more to life than

just sensation. It was her good fortune that she

agreed to suffer through that. She also showed enough

courage to bear up to that unbearable truth. By

suffering through it a new vision was born for living

for something other than sensation.

JG:

The drive for sensation is almost a hunger for perception.

AA:

Maybe. But it also could be the result of superficial

values. In many ways the CRUX project was about

the disclosure of values. What people were actually

making important in their lives. Not what they thought

they were making important, or wanted to make important,

or should be making important if and when they got

their act together. No, it showed them what they

were actually making important, whether they previously

knew it or not. Some people were shocked to realize

how dominant the force of habit was in their lives.

Others found out how dominant the force of will

was in their lives. We're not talking about one

force being better than another but two living forces

that prevail in the daily lives of people, every

single day.

Another important polarity was the more morally

charged forces of good and evil, the existing force

of good and the existing force of evil. And these,

of course, are subjective assessments as we're not

following any religious dogma or any societal definitions

of these terms. I encouraged an openness to the

existing condition of goodness within the group,

as well as the existing conditions of evil, as we

personally know and defined those terms. Good and

evil were never explicitly defined for anybody.

This was no Sunday school lesson...

JG:

The jumping off of that crux point to get the perspective

to see what I would be living for seems very daunting

to me. The cross is so much one's own incarnate

self. You surrender to your situation and live consciously

with that.

AA:

The mystery in the crucifixion archetype.

If you can get over the delusion of self-improvement

and find the courage to commit wholeheartedly to

your direct impressions of where you are the most

stuck, and really muster up the courage to continue

passing through its heart, the very center of where

you are the most stuck, without any preconception

that it's going to make you a better person, or

you're going to become free or enlightened, or whatever.

If you can get past all this nonsense and put yourself

on the line, there looms the mystery of resurrection.

Not just in the Christian sense but in the mystical

sense. Surrender doesn’t mean dwelling in your

problems. Surrender demands 100% integrity in your commitment

to following through and this carries no guarantee whatsoever.

There is no concept or image to describe how that

will turn out or how that will look like. It's

a genuine mystery in the way that death is a genuine

mystery. We don't know what death is until we're

there, until its happening to us. Same with life;

we don't know anything until it's happening. Truth

be told, we don't even know what's going to happen

next.

JG:

It seemed that within this group there was a high

degree of self responsibility.

People stuck with

it and continued thru the process.

AA: Safety is a very important factor. In this ritual

process, everybody pledged to be responsible for

creating their own safety. So no matter how strange

or weird things got, each person basically agreed

to play their own mom and dad. With everybody becoming

responsible for their own safety issues, there's

also a higher degree of group autonomy. Without

that high level of self-responsibility, this CRUX

lab would never have happened. And that was my main

incentive in inviting each of these people. I hand-picked

each person for the high level of motivation I perceived

in them around this very thing.

JG: Yes, I see how safety is very important. When I

experienced this work in Seattle, I saw a very risky,

almost Pandora's box kind of situation, where there

was such opportunity for psychological stuff to

bubble up, for projecting mom, dad, authority or

whatever.

AA: Trouble is, the psychological stuff of projection goes on anyways in any group process. It will always happen. The difference is that when you commit yourself to 100% accountability right from the start, you tend to look at those projections more as opportunities to begin reclaiming more authority and autonomy for yourself, rather than squander it away. Projection is also inherent to ritual evocation of archetypical processes when it’s done on purpose, as in conscious projection which involves an intentional charging of the ritual space with a certain energy.

Conscious projection is innate to evoking the forces

in a ritual that you are there to experience in

the first place. So, this intention of accountability

changes everything. If you don't do rituals (or

live life, for that matter) with the intention of

accountability, you are more prone to passive self-victimization

where you tend to only see how circumstances overwhelm

you. This immature behavior leads to feelings of

helplessness and betrayal and all the other negative

reactions a child acts out when not taken care of

and paid attention to. With the intent of accountability,

you agree to take charge of paying attention to

the child -- to monitoring your own behavior --

and taking care of the child when those needs and

fears surface.

JG:

In this group alchemy that happens, is there more

of a sense of group mind or group consciousness

developing ?

AA:

Any group unified by some purpose or reason for

being there is going to birth a group mind. I was

looking to support a very particular kind of group

mind based in self accountability and one that was

up for an adventure, a challenge. I tend to look

at any experience that expands consciousness, whether

triggered by ritual or by life itself, as an adventure.

My interest in consciousness expansion is not for

its own sake; any fool can get high. I look to it

as part of a larger development of conscience, something

I think is taken for granted in this culture. People

assume they have a conscience just because they

know how to feel guilty. Yet oftentimes this “conscience” is so socially conditioned into us as a life-constricting

reflex, it keeps us emotionally locked in a state

of low grade guilt without knowing it. This can

manifest as a kind of pesky self-consciousness,

annoying insecurities and a long-term stifling of

self-expression.

If you have not defined your own ethics yet, you've probably inherited your morals from the culture at large and/or your family. Your personal ethos define in your own terms: what's good, what's bad, what's evil, what's right, what's wrong. Experiences that expand your consciousness give you a better chance to see and realize the truths of your life and your own responses and definitions for what they mean to you. When you finally develop your personal responses to the truths you experience, you can define your own ethics and a conscience germane to the truth as you know it.

This is the

type of conscience I'm referring to. And I think

this kind of conscience isn't possible without direct

experience. If you are not experiencing life for

yourself, you may have temporarily lost the capacity

for direct experience. If you want to restore your

capacity for direct experience, you must be willing

to struggle and fight for it, for your consciousness.

If you have lost the capacity to think for yourself

and to come to your own conclusions and determine

your own definitions for things, then I think you

are more at the mercy of circumstance and the backup

programs of consensus, socially sanctioned moralities.

JG: In doing this work, what has been your primary motivation,

what compels you

to take this on, show this to people,

continue it, evolve it.

AA:

I do it to stay honest. If I don't find ways to

remind me of my own crux, I slip into cultural trance.

I'm not immune to that yet. If I can't occasionally

break cultural trance and receive deeper impressions

of direct experience, I'm nodding off with the rest

of them. I also utilize these labs to test and develop

creative ideas that sometimes bear fruit in the

areas of filmmaking and theatre.

JG: It was interesting in the film how one gentleman

mentioned that it changed

his perceptions, his sensate

perceptions of the world. Something in the process

really does get to essence.

AA:

This thing called essence is peculiar; a very misunderstood

term. As I know essence, it refers to an immutable

element of our nature. It doesn't change. It has

a predetermined quality about it, something that

was established perhaps at an extremely early age,

maybe one year old, two years old, who knows? But

I think it’s connected to the crux in that

it doesn't change. So maybe the essence is more

at the core and the closer to the surface you get

to your own experience, of your own self, or even

of an entire society, the more things noticeably

change.

I think as you grow more aware of what is essential

to you, it's easier to relate with what is most

essential in others. And there's a greater chance

of connecting on an essence to essence level with

others, which I find very satisfying. I think part

of what CRUX did was engage people at various degrees

of essence. When I say various degrees, I mean in

proportion to the degree of commitment each person

showed to surrendering into the immobilization that

sometimes comes with the crucifixion archetype.

To some people, immobilization means death. It's

just the worst thing imaginable, the most unbearable

thing, to be stuck. Others find a little more comfort

with this. They find their own place in this immobilization

and reach through the center of that. These individuals

tend to integrate their crux a little sooner, I

think. And then there are those who genuinely define

themselves by motion and change. The slippery characters.

For

this CRUX lab, we appointed ourselves nicknames

to symbolize our crux. One person called himself

Slippery. I think he exemplified an important drama

around confronting his own slippery nature and how

through brutal self-honesty, he was able to drop

down into something less slippery by calling himself

on it.

excerpted from

TOWARDS AN ARCHEOLOGY OF THE SOUL

(Vertical Pool Publishing, 2003) by Antero Alli

3-MINUTE EXCERPT FROM THE VIDEO

6-MINUTE EXCERPT FROM THE VIDEO

ANTERO ALLI

...ANTERO has been creating original performance works using paratheatre processes since 1977 and, has been producing experimental video documents and feature fiction films since 1993. His paratheatrical work is documented in his book, "Towards an Archeology of the Soul" (Vertical Pool, 2003). Alli's 2005 docufiction feature, "The Greater Circulation", incorporates a paratheatre performance in a critically acclaimed cinematic treatment of poet Rainer Maria Rilke's "Requiem for a Friend". His 2008 experimental feature, "The Invisible Forest" (2008; 111 min.) explores the radical ideas of French Surrealist, Antonin Artaud.

...ANTERO has been creating original performance works using paratheatre processes since 1977 and, has been producing experimental video documents and feature fiction films since 1993. His paratheatrical work is documented in his book, "Towards an Archeology of the Soul" (Vertical Pool, 2003). Alli's 2005 docufiction feature, "The Greater Circulation", incorporates a paratheatre performance in a critically acclaimed cinematic treatment of poet Rainer Maria Rilke's "Requiem for a Friend". His 2008 experimental feature, "The Invisible Forest" (2008; 111 min.) explores the radical ideas of French Surrealist, Antonin Artaud.